The American Psychological Association defines misinformation and disinformation as follows:

Misinformation is false or inaccurate information—getting the facts wrong. In other words, a mistake.

Disinformation is false information which is deliberately intended to mislead—intentionally misstating the facts.

We've been hammered with disinformation since Donald Trump first began his campaign for the presidency. But in our highly educated enclave of Chapel Hill/Carrboro, we use those terms without really believing anyone in our community could be so deceitful. In our community, we inherently believe we can't be fooled with disinformation because we believe in facts and truth. If only that were true. We can all be fooled. The challenge is to become more critical readers and listeners.

The National Endowment for Democracy says "Analysts generally agree that disinformation is always purposeful and not necessarily composed of outright lies or fabrications. It can be composed of mostly true facts, stripped of context or blended with falsehoods to support the intended message, and is always part of a larger plan or agenda."

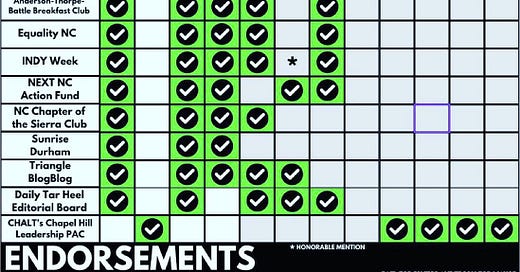

Here's a simple example of how this year's election is being overrun with disinformation.

Certain candidates attempted to place a similar handout on the Democratic informational table during early voting on Friday, but were rejected due to all the errors. By that evening, the handout shown above began circulating.

What's wrong with this handout?

It clearly states "This table only includes organizations that opened their endorsement processes to all candidates." Evidence to the contrary:

Five out of 5 of the non-endorsed candidates did not receive questionnaires or any other communication from the NEXT Action Fund or Triangle Blog Blog (TBB), the two most active and public distributors of election information this year.

CHALT has not issued endorsements. Using the negative image of CHALT by many in the progressive community, including them on this handout functions as an anti-endorsement for the candidates mistakenly shown as having received an endorsement.

At least one of the endorsements, Sierra Club, came out of a biased process that led to at least one member of the endorsement committee resigning. While that is an organizational problem the Sierra Club must address internally, it still promotes a “fair” process when it was not.

The campaigns distributing this handout were notified on Saturday of these misrepresentations, but they continued distributing it. That intentionality, knowing the information is not accurate, is what makes this disinformation.

How do you know if something is disinformation?

First and foremost, you need to reflect on your own willingness to embrace negative reviews of candidates/information you do not know or haven't reviewed independently. Confirmation bias is "the tendency to interpret new evidence as confirmation of one's existing beliefs or theories." If you can't challenge your own internal biases, you won't be in a position to challenge disinformation.

The Johns Hopkins Library offers these additional suggestions:

Ask yourself what the document owner has to gain by circulating the document

Always validate or confirm information on individuals, institutions or groups, and countries that you find on the Internet

If you don't know who wrote what you read or why they wrote it, you don't know if it's trustworthy.

We can all be fooled. The challenge is to become more critical readers and listeners.

I hope all high school teachers are including media literacy in their curriculum. This needs to me taught.

Although we do not endorse candidates we were one of the first news sources to question all of the candidates with 100% response. We have maintained endorsements and Op-eds from both sides. Please acknowledge our efforts. Michelle Casselll, Managing Editor, The Local Reporter